Book Review: Haunted Bauhaus by Elizabeth Otto

- schiffnerhs

- Jan 26, 2021

- 3 min read

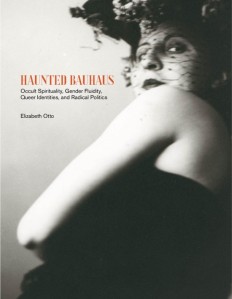

Elizabeth Otto. Haunted Bauhaus: Occult Spirituality, Gender Fluidity, Queer Identities, and Radical Politics. MIT Press, 2019.

Book review by Katherine Allocco (Western Connecticut State University)

In Haunted Bauhaus, art historian Elizabeth Otto, who has published numerous books on the Bauhaus, turns her expertise to examining some of the movements and ideas that appeared on the margins of the Bauhaus yet widely influenced the school’s development. She analyzes both recognizable Bauhaus artists and those who were lesser known to expand our understanding of the artistic vision of Bauhaus artists. By contextualizing her observations within the history of Weimar Germany, she demonstrates how the Bauhaus can be viewed as simultaneously inclusive of and exclusive to artists outside of social conventions. Throughout each chapter, Otto has included dozens of reproductions of Bauhaus artwork which she skillfully analyzes and uses to illustrate her points effectively.

After her excellent introduction that clearly defines her terms, concisely explains her argument and its significance as well as persuasively tying her analysis to the restrictions of Weimar culture and politics, Otto begins her examination by studying the influence of the occult on Bauhaus artists. She takes her readers through the various genres of occult influenced art explaining their methods and importance including spirit photography, ink wash and watercolor. Otto introduces some of the most influential leaders and teachers of the Bauhaus movement explaining their relationship with each other and with their students. Although occultism was not directly encouraged by the established faculty, she demonstrates how its ubiquitous presence coupled with the experimental nature of the school opened up the space for many students to include some interrogation of the supernatural in their projects.

In the next few chapters, Otto turns her attention to gender and sexuality, analyzing the complex and ingenious ways that artists questioning society’s gender roles, their own gender and sexuality and those wishing to queer Bauhaus art created artworks that explored these various themes. Sustaining a strong contextualization of the historical time period, she really looks at the shadow of World War I and rising fascism to analyze masculinity and the larger political and cultural context. In her chapter about Bauhaus women, she offers such original analysis of women’s’ photography, film and design, making especially strong argument through her use of Ré Soupault’s work. Otto’s analysis of Marianne Brandt’s photographic self-portraits demonstrates a very sophisticated analysis of the ways that her art challenged and redefined women’s depiction in the arts. In chapter 4, she takes disparate threads and weaves together a clear picture of the complexities of being queer in Weimar Germany. She makes it very clear that there were several marginalized Bauhaus artists who had to code and hide their impulses but were often able to use their art to do so successfully. Otto concludes her monograph with a chapter dedicated to politics as Nazism began to spread throughout Berlin and Germany and dramatically changed the artistic climate in which the Bauhaus had been operating. She shows how the specter of Nazis and politics in Germany in the 1930s inevitably redefined and forced the Bauhaus both into the center and the margins.

Consistently thorough yet succinct, this book should also be praised for its excellent writing and structure. Otto’s well-paced narrative takes readers through a focused analysis of the significance of all aspects of Bauhaus artistic output drawing from an impressive breadth of diverse sources. She has analyzed artwork, personal letters, archived documents and political propaganda, concluding that the Bauhaus needs to be understood as so much more than an architectural movement. She humanizes the artists and their work noting how they struggled with an increasingly restrictive government whose narrowing ideals about gender and sexuality pushed these artists to use their art for personal reclamation.

Otto’s book would be excellent for undergraduate or graduate courses on 20th century art history, a history course about Germany or the era of the World Wars, sociology, or gender studies. This book would also work very well in a freshman first year experience class that teaches students how to analyze visual images and archival texts and/or how to construct academic arguments and write persuasively. This book does not require prior knowledge of the Bauhaus artistic movement and can be enjoyed by anyone who is interested in reading about a generation of individuals who found their voice within an increasingly prohibitive political climate.

Haunted Bauhaus is the winner of the NEPCA’s 2019 Peter C. Rollins Book Award.

Comments