Award-Winning Book: Lust on Trial

- schiffnerhs

- Nov 4, 2019

- 3 min read

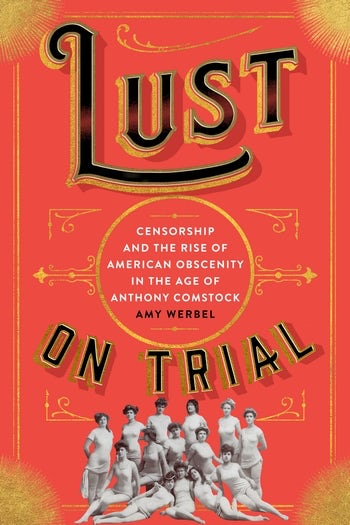

We are exuberant to announce this year’s winner of the Peter C. Rollins Book Prize: Amy Werbel’s Lust on Trial: Censorship and the Rise of American Obscenity in the Age of Anthony Comstock. New York: Columbia University Press, 2018. pp. 391.

Here is a review by Katherine Allocco (Western Connecticut State University)of this book which will be formally recognized at the 2019 NEPCA Conference on November 15-16, 2019 in Portsmouth, NH.

Amy Werbel’s excellent new book analyzes the vast changes in American values and sexual mores from the 1870s through 1915 by thoroughly investigating the role of Anthony Comstock and his war on obscenity during this era. She offers readers a comprehensive analysis of American culture in the Gilded Age with a special focus on New York and the Northeast. She argues that Comstock’s overzealous and relentless attacks on modernity only undermined his goals of eliminating vice by drawing more consumer attention to emerging art, and by creating a backlash to his old-fashioned puritanical outrage that increasingly fell out of step with modern American culture.

Throughout the book, Werbel examines Comstock’s life and his career, which spanned over forty years. With great detail and compassion, she describes his unpleasant childhood in New Canaan, CT during which he was shaped by an evangelical community that surely fueled his obsessive anti-sex worldview into adulthood. In 1868, now a veteran of the Civil War, Comstock moved to New York City to pursue a career. He worked initially for the YMCA and as he became increasingly fixated on rooting out vice, insinuated himself into a number of organizations including the US Postal Service. Comstock sought out any ally that would aid him in his war against sexuality, obscenity, and lewdness as he understood it. In 1873, he founded the New York Society for the Suppression of Vice which seemed to operate in its own legal sphere and allowed him to enter private homes and businesses that he suspected promoted immorality. Comstock’s zeal and rigidity guided him through decades of raids, seizures, and outright destruction of mail and private property. He was responsible for the promulgation of several anti-obscenity laws that led to the legal confiscation and destruction of millions of artworks, books, letters, medical tracts, and sex toys. He often boasted about these numbers and about the amount of arrests he was responsible for (supposedly thousands), and even about the number of “depraved” individuals that he had driven to suicide.

The greatest strength of Werbel’s book is her research and analysis. She examines her topic through as many facets as possible: social, cultural, economic, religious, political, and sexual. She analyzes Comstock’s mission and influence by digging deeply into the structure of American society, examining demographics, patterns in urban neighborhoods, and trends in theater and public entertainment, public sexual discourse, and evolving medical practices. Her book provides readers with a rich understanding of New York City’s history,and the many prominent individuals who found themselves in Comstock’s sights after speaking out against his crusade, including such notable women activists as Victoria Woodhull, Margaret Sanger, and Emma Goldman.

Werbel’s sources include many contemporary writings including Comstock’s own diary, his three-volume Records of Arrests, and his various treatises preaching against vice. She reproduces 19th-century paintings, photographs, and political cartoons to illustrate the sources of Comstock’s particular anxieties. Her analysis of these images and pieces showcases her expertise as an art historian and allows the reader to evaluate the so-called corruptive qualities of these pieces. She pours through volumes of primary sources from this era and uncovers traces of Comstock’s activities and ideologies throughout.

Comstock’s influence began to wane in 1884, at which point several influential (and often wealthy) leading citizens undermined his credibility and also began to openly support more modern and open-minded cultural leaders and artists. Werbel contextualizes his fall within the larger social and economic changes in American culture at the turn of the century noting that his stodgy Victorian values were increasingly challenged and rejected by a growing number of Americans from a myriad of social classes and backgrounds.

It is only in the conclusion of her book that Werbel reveals her current anxieties. In the 21st century, as the separation between church and state crumbles in the US and American women quickly lose basic rights, Werbel reminds readers that censorship and extremism are not effective tools for obtaining political or religious purity. Comstock was, after all, unsuccessful; his efforts endangered women’s health and economic stability and also appeared to promote vice rather than suppress it.

This book would be excellent for an American Studies, Urban Studies, Women’s Studies, History, Art History or Religion class. It is also broadly appealing and enjoyably readable for a wider audience.

Comments