Book Review: Camera Man (2022)

- schiffnerhs

- Jul 6, 2022

- 3 min read

Updated: Apr 17, 2025

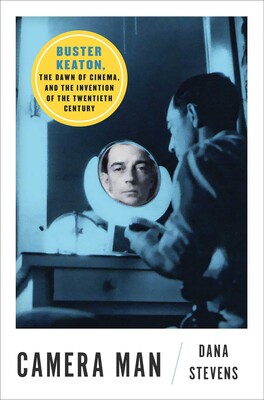

CAMERA MAN (2022)By Dana StevensAtria Books, 393 pages + notes

Charlie Chaplin was early cinema’s king of comedy. After that, it’s a tossup between Harold Lloyd and Buster Keaton. Dana Stevens, a film critic and podcast cohost for Slate, champions Keaton, of whom she is an unabashed fan.

As Camera Man’s subtitle suggests–The Dawn of Cinema and the Invention of the Twentieth Century–Stevens reaches beyond a blow-by-blow analysis of Keaton films. Not that the latter is even possible; some of his one-reel films are considered lost. Stevens situates Keaton within deeper connections between popular culture and its historical context, a strategy that sometimes drops Keaton from the limelight and into the background of events that helped define the twentieth century, including labor upheaval, reform movements, vaudeville, world war, technological change, anti-Semitism, racism, the power of print media, surrealism, and the triumph of big business. Hers is also a personality parade of cultural icons synonymous with the shift from Victorianism to modernism: Henry Ford, D. W. Griffith, William Randolph Hearst, Ernest Hemingway, Louis B. Mayer, Mary Pickford, Mabel Normand, Mack Sennett, Irving Thalberg, Bert Williams, etc.

Joseph Frank Keaton–dubbed Buster–began performing in vaudeville at the age of three with his parents, Joe and Myra. Theirs was an act that would shock those of delicate sensibilities. Laughs were milked by Joe hurling his son across the stage with such force that Buster was dubbed “the boy who can’t be damaged.” When alarmists sought to end such endangerment, Joe Keaton defiantly responded, “He’s my son and I’ll break his neck any way I want to.” Eventually, things got out of hand; Joe descended into alcoholism, Myra briefly left him, and Buster ascertained that a new entertainment platform doomed vaudeville: motion pictures.

Buster’s movie career soared when he befriended Roscoe “Fatty” Arbuckle. Stevens is among those who believe Arbuckle was wronged. Actress Virginia Rappe died at a 1921 party at Arbuckle’s home; he was charged with rape and manslaughter, and, after three trials, was acquitted. Nonetheless, his career lay in tatters. Keaton fared better. The years 1920-28 saw Keaton make silent films that established him a star, including three now considered silent film masterworks: Sherlock Jr. (1924), The General (1926), and Steamboat Bill (1928). Stevens argues that Keaton’s move to MGM in 1928 was a misstep and I agree. Camera Man, the MGM film that lends its name to the book, is practically unwatchable.

Unlike Stevens, I only partly blame MGM. Film fans know that “talkies” took off in 1927. Keaton made several more silent films before shifting to talkies, but Stevens and I part company on why Keaton’s post-1928 movie career foundered. Keaton was a brilliant physical comedian who did outrageously funny things far more dangerous than being hurled across the stage. Watch him ride backwards in a driverless motorcycle in Sherlock Jr. or stand in the door of a house falling down in Steamboat Bill Jr. Eithercould have maimed or killed him. Yet he was so nonchalant that he was dubbed the “Great Stoneface.”

However, this sort of comedy had its season. The 1930s would belong to verbal comics and Keaton couldn’t top what he did in the 1920s. As Stevens notes, Keaton tried to adapt. He was also a “camera man” in that he became a producer and director, but was he funny? Even erstwhile friends such as the Marx Brothers found his shtick shopworn and dismissed him as a gag writer. Keaton’s film work in the 1950s and 1960s was largely confined to cameo roles, and there wasn’t much noteworthy about his incessant guest turns on television (1949-66) or as a product pitchman. Stevens is correct, though, to credit Keaton with again identifying how popular culture had shifted.

Keaton’s deeper problem could be labeled “like father, like son.” Stevens details Buster’s own descent into alcoholism and attendant problems, including two failed marriages. I enjoyed this book, especially Stevens’ balance of analysis and snark. I wish, though, that she had more control over her fandom. Like it or not, the 1920s were not only Keaton’s highwater mark; they gave him license to be merely okay for the next 36 years. Still, her ability to connect the dots of change in media, politics, and popular culture is impressive. Hers is a breezy work whose substance sneaks up on readers and could work well in film history and cultural studies classes. It sure could use an index, though.

Rob WeirUniversity of Massachusetts Amherst

Comments